In a culture where there is a clear divide between those who just want to “stop being sooo politically correct” and those who want to make sure they are being respectful, it can be challenging to know what to say (and what not to say). It becomes even more of a challenge when you are attempting to talk about a population of people or a person in particular, and you are not 100% sure on the right terminology to use.

So, hopefully this post will clear things up a bit when it comes to discussing a person with a disability and why this topic matters.

So first—why does what you say matter? Language is one of the most significant indicators of emotion. Language dictates how you process the thoughts, feelings and actions of another person in your brain. Language is used in gathering your perception of others and your environment.

Language directly affects how you treat others, because it demonstrates how you think about them.

Historically, people with disabilities have been (wrongfully) perceived as weak, pitiful burdens in our society. From the “handicapped” label first used to describe homeless veterans with (what we now know as) Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, who were sitting on the street with their “caps in hand” asking for money, to the middle-schoolers (and many adults) using the “R word” to make fun of their friends when they are acting stupid, our society has made it very clear that it was deemed socially acceptable to stigmatize people with physical and mental differences.

I have worked with the disability community for over a decade. In seeing many challenges my clients faced involving the legal system, I decided to go to law school. I am a law student, and I complete my studies this August. In my current law school program, which I have loved, I have encountered professors, classmates and administrators who (knowing our school has students with disabilities in attendance) talk about people with disabilities like trash. A professor in a class I greatly enjoy, in response to me saying I want to represent people with disabilities, said, “Oh, you want to represent the meek and pathetic.” To which I did not hide my shocked expression as he quickly moved on to the next topic.

I have many professors who are socially conscious, and respectful towards students and other people with disabilities. But, I also have heard professors refer to accommodations as “special treatment” and refer to people with mental illness as “crazies” while rotating their index finger in a circle next to their head. These are accomplished, intelligent, highly-educated professionals. Yet still, training on disability appropriateness and inclusion has not been emphasized in their studies. These are attorneys and professors who represent and teach people with disabilities on a daily basis, even if they don’t know it. They aren’t bad people. They’re just misinformed and desensitized based on societal conditioning that people with disabilities aren’t worthy of respect.

This stops right here, right now. It never was, and never will be acceptable. This is not a recommendation, but a requirement. This is a heads-up that what you say matters, and if you use offensive language you won’t be accepted, and it isn’t cool.

Over 52 million people in this country have been diagnosed with a disability—over 2 million people in Michigan (where I live).

Disability is part of the human experience. It’s not grim, but it is the truth that at some point in your life you will have a disability. If you haven’t yet, it could happen tomorrow or in 20 years. But you cannot deny that at some point, as you age, you will face trauma and change, physical and emotional. In living life, you are putting your body in a position where it wears down over time. You will experience unpredictability in your life and you will have to learn to accept it, adapt to it, and thrive with it.

In that moment, when you are likely dealing with extreme physical and emotional changes, and grieving over abilities lost and limitations imposed, would you want to be insulted or would you want to be respected? You wouldn’t want people to categorize you as a burden, or incapable, or unworthy—because you are not any of those things simply because of a physical or emotional disability.

You’d want to be seen as a person, first and above all else.

This is where the person-first language shift began. The disability community and its advocates decided that someone needed to display how to appropriately talk to and about people with disabilities.

First, you call the person by his/her name. If the disability is not relevant to the conversation, it is not necessary nor appropriate to attach it to your description of the person.

When disability is relevant to the conversation, use person-first language. Instead of saying “disabled man” say “man with a disability.” Instead of saying “schizophrenic” say “woman with schizophrenia.” It takes practice to get in the habit of using the right phrasing, but it’s important. You are literally and semantically putting the person first. This emphasizes that person, their abilities, and their individuality over any disability that might follow.

Person-first language should be your foundation. If the person with the disability prefers you to use other language or phrasing, always comply with what language they feel comfortable with, but NEVER use the “R word.”

Let’s talk about the “R word” for a minute. The word “retarded” was part of a clinical diagnosis (mental retardation), that our society deemed an insult for someone they perceived as stupid, irrational, or ridiculous. So, our society decided to use this part of the clinical diagnosis, not toward those with a diagnosed intellectual disability, but instead towards people without disabilities as a way to criticize or ostracize them.

Because our selfish, rude, and ignorant society twisted this clinical diagnosis into such a horrendous insult, the word lost its original meaning completely. The word became a weapon instead of a condition. A simple word began to carry so much hate and stigma in its delivery, that this large community of people with disabilities had to actually protest and advocate that medically and legally the word be removed.

To anyone out there who responds to a request to stop using that word by saying, “but technically I am right, because that’s what doctor’s use,” you’re wrong. You’re also (likely) not a doctor. It is not used in laws, textbooks, nor in practice. You have a brave girl named Rosa to thank for that. Rosa’s law was passed in 2010, and if you want to read the actual law that was passed, you can find it here.

Rosa was a strong, smart, driven young girl who decided that she was tired of being made fun of, and tired of others using the “R word” to make fun of others. With the support of many senators, representatives, and public advocacy campaigns, Rosa took this change in language into her own hands and asked the government to remove the “R word” from its laws. Rosa was successful in achieving this goal, after “Rosa’s Law” was signed and approved by former President Barack Obama in 2010. Additionally, after seeing the mess that was the movie Tropic Thunder, the “Spread the Word to End the Word” campaign spread the message that using the “R word” to make fun of someone in the media and socially is unacceptable.

Most importantly, if you are wondering other reasons as to why you should not use the “R word” besides it being technically incorrect, offensive, and ignorant, you just shouldn’t use it because people with disabilities don’t want you to. It’s that simple. Be a decent human being to other human beings. You will someday be in their shoes, and you’ll want someone to show you empathy and respect when that happens. But even if you are the rare exception that is not going to have a disability someday, it takes more energy to spread hateful language than it does to just be decent.

For these reasons, you also want to be really aware of how you perceive people with disabilities. This is where it can get tricky for many people without disabilities, because you may not be using words that you find to be offensive, but you are inadvertently mislabeling or stereotyping a person with a disability.

You may mean well when you say someone is “inspiring” simply because they are living with a disability. But when you say that someone is inspiring for doing things that a person typically does each day, it’s more than a little condescending. We know, you are acknowledging that there may be more things a person with a disability has to do to achieve the same results you can in your day-to-day activities. But when you say that someone is “inspiring” or “overcoming her disability” in doing typical daily functions, you are also sending the message that her life is so awful and unimaginable, that she must have to overcome her horrible circumstances. Don’t be patronizing. Be respectful.

What does it boil down to? People with disabilities don’t want your pity or sympathy. They want your respect and empathy. When you say someone is “suffering with…” or “overcoming…” or “confined to/by…” you are invoking feelings of pity, your inclination is to feel sorry for that person. It’s like saying, “his life is so awful, he is suffering/overcoming/confined by his disability.”

Instead, you can use (when the disability is relevant) “sustained a brain injury,” “diagnosed with…” or “living with (insert disability here).” This language normalizes disability, instead of dramatizing it. Disability may be part of that person’s life, but it’s not their whole life and it certainly is not who they are. People with disabilities adapt to their differences, or even utilize their differences to become successful.

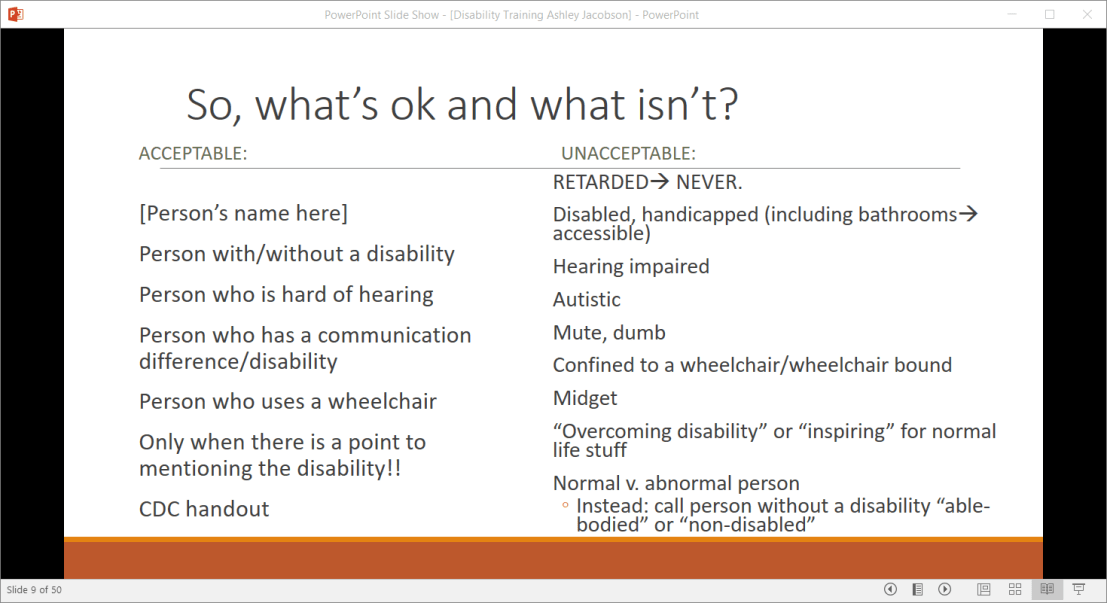

I appreciate those who have stuck with me here. This is a good cheat sheet I use in many of my presentations:

Also, keep in mind that certain disability populations take pride in their label because they do not see it as a stereotyped label but instead use the term as a way of indicating a community of like-experienced individuals. Person-first language should always be your starting-point—your foundation. As I stated earlier, if the individual states he wants you to refer to him in another way, it’s okay to refer to that person using the term he has provided. Always start back at these guidelines though with new people that you meet.

Thank you for caring and sharing.

Ashley Jacobson, MA, CRC

legallyabled@gmail.com

Thank you for your post! I was born with a disability and can really relate to this.

https://theoneandonly346255562.wordpress.com/

LikeLike

You’re welcome! I am happy to hear you found it helpful. I love connecting with people with disabilities, so feel free to reach out any time!

LikeLike